Everything you were never told about strength, cuts, sound, and durability!

If you play the saxophone or the clarinet, you know the ritual. You open a brand-new box, tear the cellophane with a mix of hope and anxiety, pull out that small piece of wood, and place it on your mouthpiece while praying to the gods of music. Sometimes a miracle happens: the sound flows, the highs are sweet, the lows are deep, and you feel like you’re flying. But other times… other times it’s like trying to blow through an ironing board, or worse, it sounds like a sick duck.

It’s the most complex, frustrating, and rewarding relationship in the life of a woodwind player.

We often spend fortunes on vintage mouthpieces, gold-plated ligatures, and necks made of exotic materials, forgetting that the true sound generator, the real engine of our voice, is a plant-based strip that costs just a few euros. Without the reed, your instrument is nothing more than an inert sculpture of metal or wood.

At Odisei Music, and in the musical community at large, we know the topic of reeds is surrounded by myths, misinformation, and a lot of superstition. That’s why we’ve prepared this massive guide. Not just to explain what the numbers mean, but to help you understand the physics behind your sound so you can stop throwing money away on boxes that don’t work for you.

Whether you’re a clarinetist searching for the perfect dark orchestral sound, or a tenor saxophonist looking to roar in a rock band, this is everything you need to know.

Before talking about numbers and cuts, let’s talk botany. The vast majority of “traditional” reeds are made from Arundo donax, a giant cane that grows wild in Mediterranean climates. Although it’s cultivated in places like Argentina and Spain, the “Mecca” of reeds is the Var region in southern France.

Why does this matter? Because it’s crucial to understanding your frustration. Reed cane is an organic, living material. It’s not plastic molded in a sterile factory. Each reed comes from a plant that was exposed differently to wind, sun, rain, and soil. Even within the same cane tube, the fiber is denser at the base than at the tip.

That’s why when you buy a box of 10 reeds, you’re buying 10 unique pieces of nature. It is physically impossible for them all to be identical. Accepting this natural imperfection is the first step toward suffering less and managing your tools intelligently.

2. Strength: destroying the myth

Let’s enter the most controversial territory: the numbers. 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5… There’s a toxic belief in conservatories and music schools that equates reed strength with masculinity or musical quality. “You’re still on a 2.5? I’m already on a 4.” If you’ve heard this, ignore it. It’s nonsense.

Many people mistakenly believe the number refers to the thickness of the wood. False. A 1.5 reed has exactly the same external dimensions as a 5. The difference lies in fiber density and the resistance it offers to vibration. A lower-number reed is less dense and more flexible; a higher-number reed is denser and stiffer.

GYM analogy

Think of playing the sax or clarinet like going to the gym. The reed is the weight you lift. On your first day at the gym, you don’t try to bench press 100 kilos. If you do, you’ll get injured, adopt terrible form, and fail the exercise. It’s the same with your instrument. Your embouchure (the muscles around your mouth) needs trainin

- Beginner (1.5 – 2.0): You need a reed that vibrates with the slightest breath. This lets you focus on finger placement and learning to breathe without fighting the instrument.

- Evolution: As you play (months, years), your facial muscles strengthen. Suddenly, that 1.5 reed starts sounding shrill, closes off when you play loud (the sound cuts out), and the intonation becomes unstable. Congratulations, you’ve outgrown that reed. Time to move up to a 2.5.

- Professional (2.5 – 3.5+): This is where most professionals settle. The goal is NOT to reach a 5. Playing a 5 is like trying to make a floorboard vibrate. Most great jazz saxophonists play medium strengths (2.5 or 3) because they seek flexibility, not stiffness.

How do you know if your reed is wrong?

- Too soft: The sound is very bright and nasal (duck-like), high notes go flat, and if you blow hard, the reed sticks to the mouthpiece and the sound stops.

- Too hard: You hear a lot of air (fuzz), you’re exhausted after five minutes, you bite your lower lip to compensate, the sound is dull, and playing pianissimo is impossible.

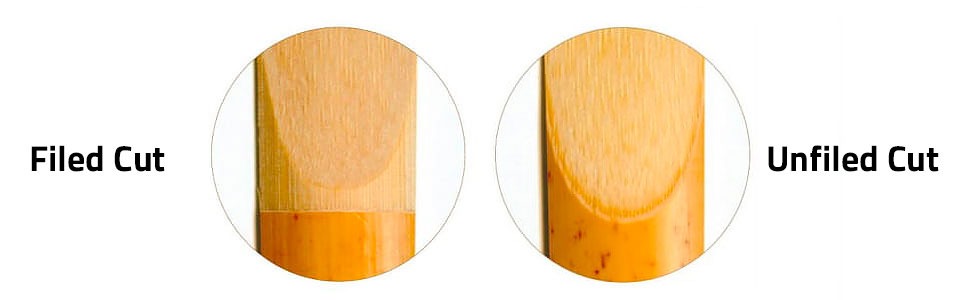

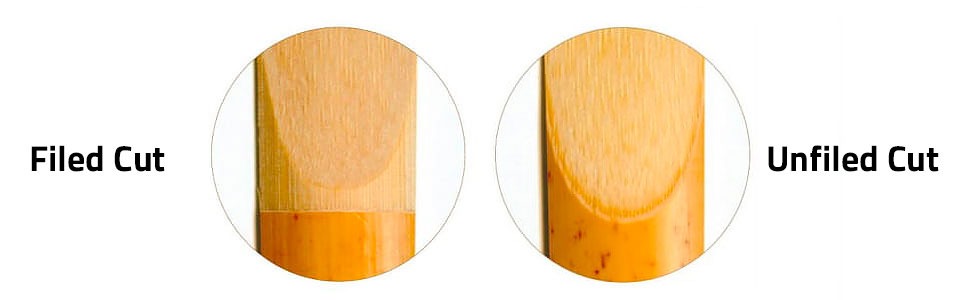

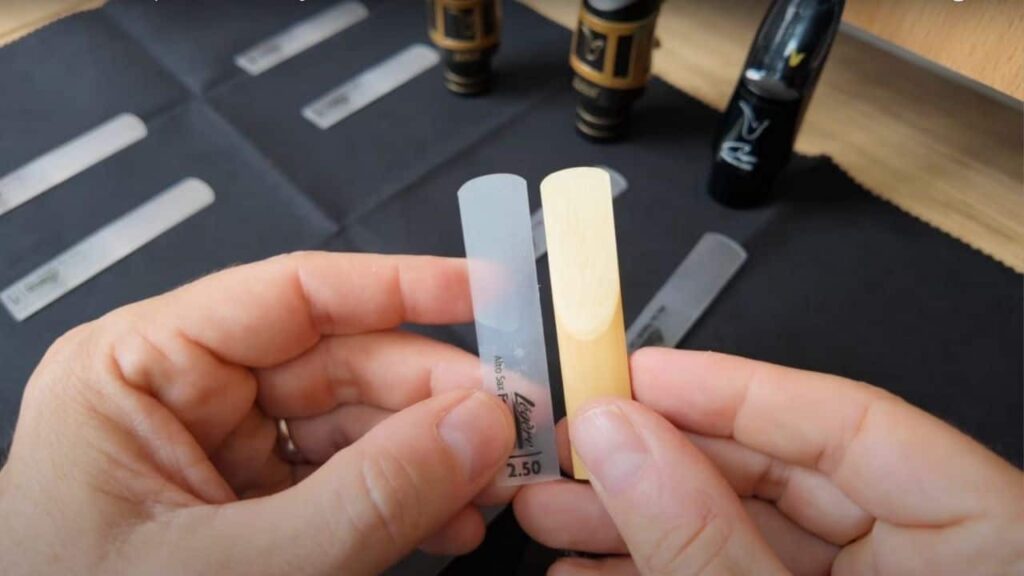

3. Anatomy of the cut: filed vs. unfiled

If you’ve ever frozen in front of a shop shelf staring at a box of D’Addario Select Jazz “Filed” and another “Unfiled,” this section is for you. The difference is visually obvious but acoustically subtle.

Unfiled (american cut)

When you look at the reed, you’ll see the bark (the shiny, dark part) forming a “U” shape that blends smoothly into the scraped area. By leaving more bark at the base, the reed retains more rigidity in the stock (the part held by the ligature). It offers more resistance, something solid to push against. This often produces a darker, more robust sound with lots of core. It’s popular among players seeking a powerful, traditional American jazz tone or orchestral musicians wanting density.

Filed (french cut)

Held up to the light, you’ll see a clean, straight horizontal line where the bark ends, as if it’s been sanded off. Removing that strip releases tension in the outer fibers, making the reed freer and quicker to respond. With less material holding back vibration, response is immediate. The sound is often slightly brighter, with more upper harmonics and an easier “buzz.” This is favored by many classical clarinetists (for clarity) and pop/funk saxophonists who need speed.The difference is more about feel (what you sense in your mouth) than what the audience hears. If your reed feels dull or slow, try a filed cut. If your sound feels too thin, try unfiled.

4. Classical vs. jazz profiles

Beyond filing, what truly defines a reed’s character is its geometric profile, the relationship between the thickness of the heart, die tip, and the rails.

Classical design (Vandoren V12, D’Addario Reserve)

Classical players seek purity: a sound that blends, remains even across registers, and allows ultra-precise articulation. These reeds typically have a thick heart and a relatively thick tip. The thick heart provides darkness and stability; the thicker tip demands firm, precise articulation. Bending notes is difficult, but intonation is impeccable.

Jazz / modern design (Vandoren Java/ZZ, D’Addario Select Jazz, Rico Royal)

Jazz and rock players need projection and color. They want the sound to break a little, to have grit or brightness that cuts through drums and electric guitars. These reeds often have a thinner heart or a steeper slope toward a thinner tip. The thin tip vibrates wildly, generating bright harmonics. The reed is more flexible, allowing wide vibrato, subtones, and effects.

Can I use a classical reed for jazz? Absolutely. There’s no reed police. David Sanborn, one of the most influential pop/funk saxophonists ever, used Vandoren V12 (classical) reeds for years because he loved their percussive attack. Many modern clarinetists use jazz reeds for a warmer, more flexible sound. Experiment.

5. The drama of durability and maintenance

Reeds cost money, and it hurts when one dies after three days. So how long should a reed last? The honest answer: if you play daily and intensely, a living wood reed has an optimal life of 2 to 4 weeks. After that, the fibers fatigue, lose elasticity, and the sound becomes dull.

But you can extend their life (and save money):

Rotation

The number one beginner mistake is finding one good reed and playing it until it dies. Saliva contains enzymes that degrade wood, and reeds need to dry completely between sessions. Do this instead: buy a numbered reed case. Keep four active reeds. Monday: Reed 1. Tuesday: Reed 2, and so on. Each reed lasts longer, and you get used to small variations, so when one breaks, the shock to your embouchure isn’t brutal.

Warping

You’ve seen it: the tip becomes wavy like a potato chip. This happens when the reed dries unevenly. Never leave a reed on the mouthpiece. After playing, gently dry it and store it flat in a case. Use humidity-control systems (like Boveda packs or Reed Vitalizer). Keeping reeds at around 72% humidity prevents warping and means they’re always ready to play, no five minutes of soaking required.

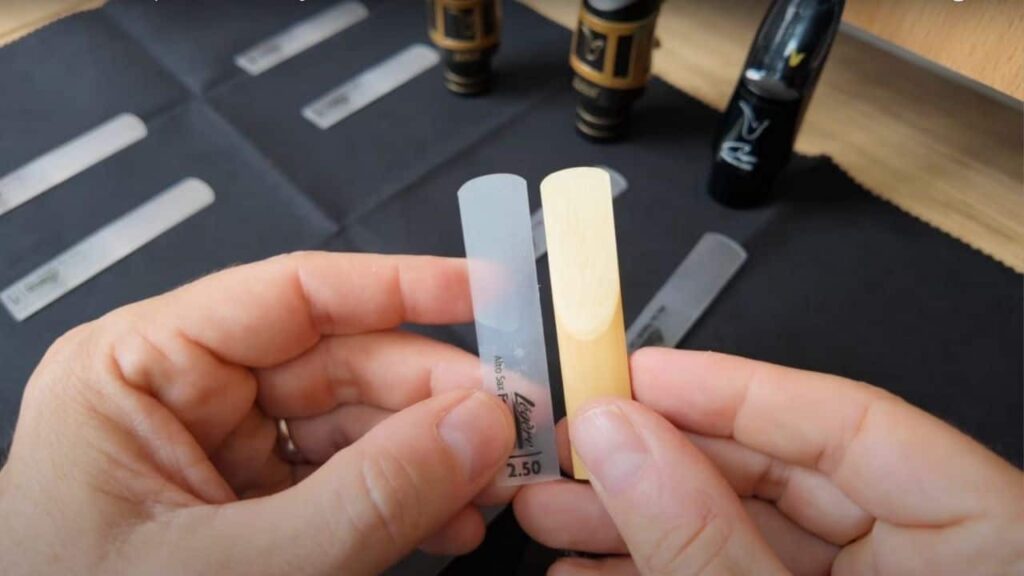

6. The synthetic revolution: heresy or the future?

Now for the hottest topic of the last decade: synthetic reeds. Fifteen years ago, plastic reeds were a joke, they sounded like cheap toys. But composite-material technology (aerospace polymers, carbon fiber, etc.) has advanced rapidly. Brands like Légère, Venn (D’Addario), Fiberreed, and Silverstein now offer products that seriously rival wood.

The undeniable advantages

- Total Consistency: Every reed is identical. No “bad reeds” in the box.

- Near Immortality: One synthetic reed can last 4–6 months of heavy use. Do the math, a €30 synthetic reed equals 4–5 boxes of cane reeds. Long-term, it’s cheaper.

- Hygiene & Convenience: They don’t absorb saliva, can be washed with soap and water, and need no soaking. Pick up the instrument and it plays instantly, perfect for doubling in pit orchestras.

The downside? For extreme purists, they still lack a small percentage of warmth. Wood has a chaotic harmonic complexity that’s hard to replicate 100%. Some players feel synthetics sound a bit “flat” or monochromatic, and the feel on the lip is different (more slippery). That said, today, on recordings or amplified concerts, it’s almost impossible to tell a good synthetic from a cane reed.

7. Survival tips and DIY adjustment

To finish, some workshop wisdom. What if a reed is too hard and you have no spare? Or too soft? Reeds can be adjusted.

- Too hard: Lightly sand the flat table of the reed on very fine sandpaper (600 grit or higher) placed on glass. This reduces overall thickness. You can also gently sand the shoulders to free vibration.

- Too soft: Use a reed clipper. Trimming a fraction of a millimeter from the tip makes the reed harder and restores life. Be careful, this changes the tip profile.

At the end of the day, the perfect reed doesn’t exist. What exists is the perfect reed for you, at this moment in your life. Your mouthpiece, ligature, mouth anatomy, and sound concept are unique. Just because your idol plays a Vandoren Traditional 4 doesn’t mean you should and trying to copy someone else’s setup is often a recipe for frustration.

We know the reed world can be confusing, so we’ve prepared an exclusive resource for you.

Unlock the secrets behind saxophone and clarinet reeds with our Reed optimization guide! From understanding why some reeds sound amazing while others fail, to learning the science of vibration, proper strength selection, and DIY adjustments, this guide gives you full control over your sound. Discover how to break in new reeds, rotate them for maximum lifespan, diagnose issues with the pop test, and even rescue reeds that seem “dead.” Whether you play jazz, classical, or rock, mastering these techniques will save money, improve consistency, and make playing far more enjoyable.